The Future of the Venture Capital Industry

The venture capital industry is in the years-long process of reinventing itself at the moment, as illustrated by the level of attention paid to the evolution of incubators and angel investing. Large deals in the tens of millions of dollars and up remain large deals, with their attendant culture and dependency on time, diligence, and the all-important personal connections, but real change in the industry focuses on how to effectively invest in smaller opportunities - how to aim for tenfold and better returns on investment of a few hundred thousand dollars or less, yet still be able to make enough of these investments to support large venture funds. A large fund implies the need for a great many small investments, yet identifying and managing those small investments is a real challenge from a manpower point of view. People who are good at managing the process of investment for a fund just aren't all that common, but if you went about things the old fashioned way, you'd need ten times as many of them to manage ten times as many investments.

Obviously adopting the practice of hiring ten times as many associates for a venture fund of a given size isn't going to happen. Innovation must occur to enable fewer investors to effectively source and manage larger numbers of small investments.

To a certain degree this present focus on innovation in the management of smaller investments is all a historical accident. The venture community centered in California was from its inception very focused on computing technology, and computing technology - and everything built on it - is going through a cost and effort implosion. Everything is rapidly becoming very much cheaper and easier. Therefore levels of investment follow that trend downward - if you want to get in early and own a usefully large amount of a nascent company, you have to invest at a level commensurate with the startup cost. That startup cost for the most talked about forms of technology may be as little as a tenth of what it was ten years ago. That forces change in the venture capital world, and so there is a degree of mixing ideas, exploration, experimentation in new business models, and other fun and games going on at the moment - and hence the focus on incubators and angels amongst the talking heads.

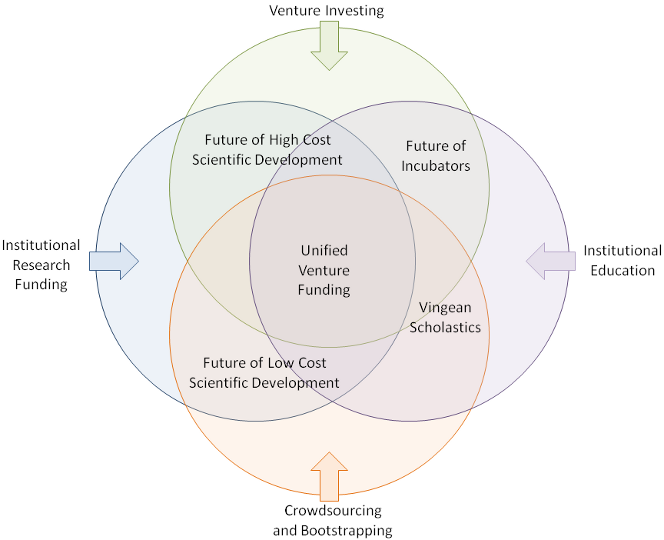

But where is this all going? I would argue that the end result of present trends will produce a new segment of the venture industry that is a functional unification of (a) the classic venture investing industry, (b) formal scholastic education, (c) institutional funding for scientific research, and (d) models and formal institutions for crowdsourced funding and bootstrapping of companies. It will draw from all of these, and exist in the space where the concepts all overlap.

The present direction of some incubators is towards the concept of schools, in the older sense of the word. To some eyes present experiments look like an early stage in the development of a new scholastic institution of practical business development. With well tuned entry requirements such an entity might serve as a filter that allows venture investment in all graduates with comparatively little detailed due diligence, trusting to the quality of the school (the filter) to raise the expectation value of these blanket investments. Experiments in this sort of model are already taking place at Y Combinator, and others will no doubt follow. If they see success, expect to see more rapid movement towards formalized schools of practical entrepreneurship, which will orbit established venture funds to act as feeder mechanisms. You might look on this as a structured, industrial manifestation of the informal process of apprenticeship and networking that always existed in the startup community - and either like it or loathe it for exactly that reason, depending on your tastes.

It is worth remembering that while venture capitalists and organized groups of angel investors can enter the space of incubators-as-schools from one side, existing scholastic institutions can just as well enter it from their side. I can't image that the traditional schools will be any good at this if they do try, given long-standing academic hostilities towards the business of being in business, but some of the younger less hidebound institutions might well be successful. Consider the present University of Phoenix, a future Khan Academy, and a range of other entities establishing their own early stage venture funds, or partnering with venture funds to do something new in this space - it isn't so far fetched an idea.

Note that a more scholastic form of incubator is, to my mind, a very different concept from what I'll call Vingean Scholastics. This is the vision put forward by Vernor Vinge in Fast Times at Fairmont High in which building startups is a part of the curriculum for all young people and at least ramen-level economic success is necessary for graduation at a high school level. Building a business, or at the least a short-term economic success, is how the students pay for school and how the schools earn their keep as businesses themselves. In that fictional near future, this is all a part of teaching young adults how to live in a world of constant, enormously rapid change driven by computational technology, in which the idea of holding down a job doing roughly the same sort of thing for five years is laughable, and everyone must know how to be an entrepreneur in order to flow with the pace of change.

But this too will come to pass, I think, with Vingean Scholastic organizations as another sort of filter to build and channel groups of startup founders - with, collectively, a positive expectation value on investment - towards future forms of venture fund.

Consider that, at the very earliest stages, starting a company to apply technology blends into the process of researching and creating that technology. There is no bright dividing line between research (or creation) and application, one side science and the other side business. If venture investment keeps pushing back earlier and earlier into the process of creation, it will come to more firmly occupy areas traditionally dominated by scientific funding institutions - and why not? If you can build a system that does a fair job of identifying research programs and researchers who will create profitable opportunities, isn't that getting into the game one step ahead of those who only focus on the business side of the house?

Outside the world of established companies with strong research divisions, the standard panoply of scientific funding institutions aren't all that interested in profit, per se. Certainly not in the same way that the owners of a business are, and indeed there is a strong degree of hostility towards profit and publicity in the scientific community. But nonetheless, companies emerge, may led by scientists to produce applications and profit from their research. Again, I'm less interested in the high value investments arena at the intersection of science and technology than in the changing face of low-cost research and development: where scientific research can easily blend into technology application and commercial development - and in a short timeframe and where significant goals can be achieved for far less than a million dollars.

When considering this end of scientific development, biotechnology is a great example of a field in great upheaval. Costs are plummeting so very rapidly that a garage industry is arising, its members producing open source and home-grown technologies that retail for a few hundred dollars apiece - devices that would have cost a hundred times that much a decade ago. The cost of significant research projects is plummeting too. A graduate student or DIYbio enthusiast can accomplish in six months and a few tens of thousands of dollars what would have taken an entire laboratory, years, and tens of millions of dollars back in the 1990s - if it was even possible at all.

Following this path, and as costs fall dramatically, we soon find ourselves in the world of crowdsourcing and bootstrapping - which is itself a whole ecosystem of experimentation, led by the computing, publishing, and coding industry and now spreading to everything else that can be accomplished for modest cost. Take Kickstarter, for example, or any one of a dozen other projects that aim to formalize or improve upon the process of raising money through patronage, ransom, and other models for collaborative fundraising. Scientific research is just as open to crowdsourcing as any other endeavor, and biotechnology is a potential poster child for new models in research organization and funding: raising money from interested members of the public for very specific projects that might cost as little as ten thousand dollars. These would be line-items in a big proposal or never happen at all, but in a crowdsourced, bootstrapped world they can be called out and funded by the people who are most interested in the results. Consider investigations into rare diseases, for example, or other projects that are typically poorly supported by the major, and very conservative, funding institutions.

Crowdsourced science funding of specific projects in this manner has taken place throughout the non-profit world at a small scale for a number of years - ad-hoc programs and one-off efforts. There are presently even a few initiatives to try to build a Kickstarter for scientific research, but the full blossoming of this concept into an industry of its own has yet to happen. It is coming, however, make no mistake: too many people are working on it and too much is already taking place at the grassroots level for this idea to just fade away.

The innovations and successes that are emerging - and will continue to emerge - from the intersection of the worlds of business and scientific crowdsourced fundraising will, I think, be adopted by the venture investing organizations that follow on from today's incubators. Entering this space will make the venture industry more able to incorporate targeted funding of research into its toolbox: more able to close the gap between late stage scientific research and early stage technology development. The organizations that evolve from this synthesis of methodologies will probably look nothing like a hypothetical mid-point average between Kickstarter, Y Combinator, and Fund Science, but will rather be something less easily anticipated - a completely new form of entity built upon these foundations, not just a direct hybrid.

The changes ahead are profound, and will take segments of the venture investment industry far farther from their roots than the experimental incubators of today. Successful realization of these new forms of venture investment will require new skill sets, new experience, and new visionaries - which will mean more cycles of investment, thought, and divergence and synthesis between differing schools of thought.

So time will pass. The world will change. But it will happen.